HEARING THE Snow falling: A GLIMPSE INTO THE SOUND DESIGN IN WALLY WORLD

A behind-the-scenes conversation with Sound Designer Aaron Stephenson and Steppenwolf marketing staff member Gin To on the sound design in Isaac Gómez’s radio play Wally World. Aaron Stephenson is a long-time Steppenwolfer who fell in love with the theater in 2010 after seeing Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and has worked in the sound department as a technician for six seasons. He recently designed and composed original music for the radio play adaptation of George Orwell’s Animal Farm.

Gin To (GT): What was your first impression of Wally World and what drew you to this project?

Aaron Stephenson (AS): I had run audio for La Ruta and I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter. So, I was already familiar with Isaac [Gómez]'s work. And I had designed for Lili-Anne [Brown] who was our co-director on a different show as well. So, I knew them. And when the offer came through, I hadn’t read Wally World yet, I just said, sight unseen, “I'll do it. If it's an Isaac play, I want to be involved. If Lili-Anne’s directing, I want to be involved.” I have so much trust in them and their work, that it was a no brainer for me.

GT: What are some of the biggest differences between sound designing for a stage production versus sound designing for an audio/virtual play?

AS: Yeah, it's definitely been a big transition. The biggest thing for me is that theater is so collaborative. And a big part of what's attractive to me about theater as an art form is that you're all in the room together. So, all of your ideas are run through a brain trust, and you're bouncing things off of each other, department to department; you're on headset with each other.

Doing an audio play is so much more isolating. Because instead of the usual process, where it's all collaborative and there’s a conversation happening, doing an audio play is a bit like being pen pals with your collaborators. You do your work, and you send it to them; they do their work, and they send it back to you. And we just go back and forth, giving each other notes and doing work until we feel like it's complete.

And so oftentimes, compared to live theater, it can be a little bit lonelier. And it's easier to second-guess yourself, because you don't have this group of people to go, “that's great,” or, “that doesn't really work. Let's try something different.” You have to do big chunks, and then send it all and wait for that feedback. So, there's definitely been a paradigm shift in what your workflow is like, because you aren't doing it all together at the same time.

GT: Are there certain blessings to the shift in format? Something you enjoy about designing audio play?

AS: As a sound person, it's a double-edged sword. It's great because I have so much more design control! But it's also, you know, I have so much more design work to do. [Laughter] All of a sudden, I'm doing the design work of all the design departments, things like doors closing. A lot of these things would be taken care of just by being in the physical space. You have a set designer who builds these things and a prop designer who makes phones ring and a lighting designer who tells you that the sun is rising. Suddenly in an audio play, everything is sound; you don't have sunlight to tell you the sun's rising, you have to hear it. And the door closing, footsteps, and things that you wouldn't normally think about now have to be added in in post-production.

Now, there are pockets of the play where you're like, “why does this seem empty?” And it's because a person would be crossing the stage at that point. But you can't hear them walking. All in all, there are little details that you wouldn’t think about normally as a sound designer. But now they are your responsibility. So, it's great, because I get to choose what their shoes sound like. But I also have to choose what their shoes sound like!

GT: It’s fascinating when you talked about the sound of the sun rising because I have no idea how I would even start to accomplish that. Are there specific moments in Wally World that required you to be creative in building the world through just sound?

AS: Without giving too much away in terms of spoilers, there's a moment where it's supposed to sound like it's snowing. And if you've ever stood in the snow, the sound of snowing is silence. It's really quiet. How do you convey that to a listener’s ears that it's snowing?

And then there's also a moment—a romantic moment— where you don't want to just hear the sound of smooching in your headphones. [Laughter] That might be off-putting, and it might take the romance away, because it's almost too literal. So how do you convey a romantic moment just for someone's ears without them being able to see it happening? It's small things like that that we took for granted. And we must now find creative ways and musical ways to depict.

GT: What are some challenges specific to this play?

AS: One of the big challenges of this play is that it takes place inside a store. How do you convey changes in time and place? How do we know that time is going by? How do we know that we're moving to a new spot, just through audio? Being in a superstore is a bit like being in Las Vegas. There’s no clocks, no windows; they want you to stay in and keep shopping! This means we have to find creative ways to let the listeners know where in the store the characters physically are.

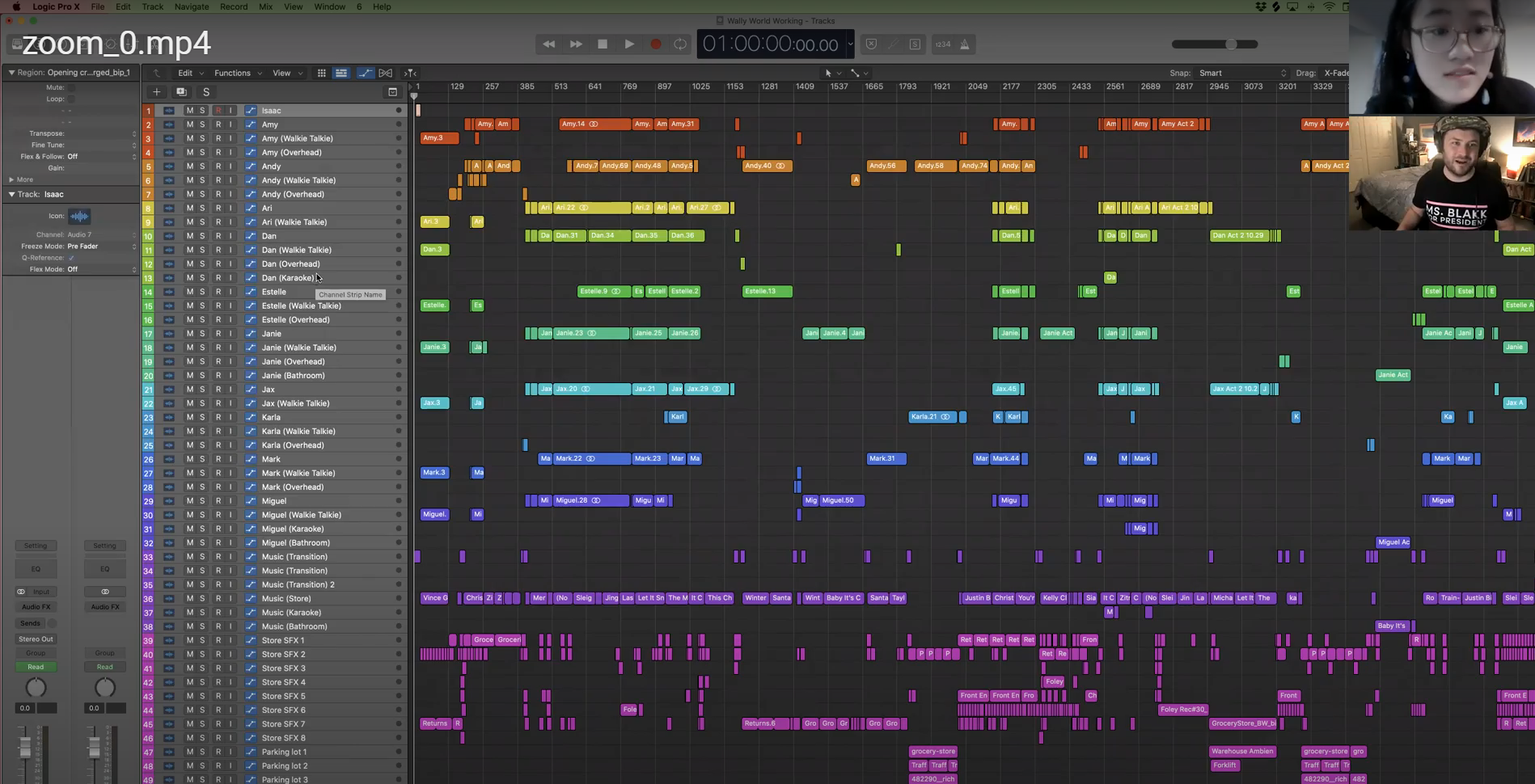

So, we recorded actors speaking in different ways, depending on what’s going on with their character at any given moment. For example, we have Amy, Amy on a walkie talkie, Amy on the overhead speaker; we have Dan and Dan karaoke mode; we have Janie and her in a bathroom because depending on where they are, their voices have different quality to them. Another way to indicate change in location is through music. You can have music playing and then suddenly, there’s a blip to indicate that the characters go outside briefly. During the recording period, I also masked up and went to a big superstore with my little recorder and just recorded sound around the store to get samples in different areas. The grocery aisle doesn’t sound the same as the check-out area or the returns area. We need all these different sounds to communicate that the characters are moving around a very big store.

GT: What is your process of selecting the music?

AS: I feel lucky to be paired up with Isaac as a playwright, because he's very specific in his writing. In this play, names of scenes are also the names of Christmas songs. So, it was cluing me in to what—if not that song—the tone of a scene should be. And then like any design, it's a lot of trial and error. I have what it sounds like in my head; I try and build that. I would send that to Lili-Anne and Isaac, and they would give a thumbs up or thumbs down on the decisions I've made, and we go from there.

GT: What was the recording process like?

AS: It’s kind of unique. Normally, as a designer, you're less involved with the rehearsal process. And for this show, because the timeline to produce was so compressed compared to a normal stage production, I was pretty involved. I was there for the one-week workshop, and then for the two five-day weeks. So, ten days of actual capture, of recording the actors. Just being able to have a voice in that room, along with the directors, was kind of unique for me. We had to use our time wisely because we only had two weeks to get everything that we needed. Because when we go into post-production, if anything was missed, the backend work becomes much more complicated trying to find a way to fix it. So, during the short period of time that we had the actors, we had to be meticulous and asked for different interpretations in case we change our mind later about what a scene should sound like.

GT: How did that feel from a designer’s point of view?

AS: As a designer, it was empowering to be a bigger part of that creative conversation. Usually, sound designers have less creative control because we aren’t in the room throughout the whole process. So being more involved this time was fun for me! I got to put my director hat on. Like, an assistant assistant director, you know? [Laughter].

Something I really love about theatre is that when you're doing a live show, things change performance to performance. Because actors and production crew are humans! There’s always going to be that human element. But in this new format, what’s great is that we have so much more control. Everything can be made so specific; the timing of cues can be made so much more specific because you are the ones to package the final product. And so, we can be very precise in our choices in a way that you can't be sometimes in theater.

GT: Anything else you want to share before people listen?

AS: You know, normally in Christmas season, you'd be hearing Christmas songs everywhere. So, I hope that this audio play gives you a little taste of the holidays.

STEPPENWOLF NOW

MADE IN CHICAGO. STREAMING EVERYWHERE

Wally World is one of six virtual productions on the Steppenwolf NOW virtual stage. Get access to all six productions with the purchase of a virtual membership for only $75. Discounts available for essential workers, artists, students and teachers.